For those of a certain age, it is impossible to forget how consumed the American public was with the Vietnam War in the late 60s and early 70s. We ate it, slept it, watched it on TV every night. But not me – I was a student in a state of denial for most of its duration, even though many of my high school classmates were fighting and dying there.

Afterward, when Michael Herr’s “Dispatches” burst upon the world in 1977, providing gritty literary bulletins about what it had been like to be deep inside the War, I ignored that, too. I just didn’t want to know. Now I’m traveling to Vietnam for the first time, thinking about what my brethren went through, what Vietnam herself went through. I’ve got a lot to catch up on and atone for. For what they’re worth, then, here are my dispatches, 40 years too late …

Flying west from New York to Hanoi, the sun doesn’t set in the ordinary manner but boils on the horizon for minutes on end, beckoning us to catch up …

WHAT’S IT LIKE FOR A BOOMER who avoided the Vietnam War to finally face up to that Land of Awful Names: Da Nang, My Lai, Khe Sanh and others? I’m long overdue to find out. Just seeing the word "HANOI" on the destination board at JFK makes my heart thud. Hanoi — the city where John McCain was tortured and detained for five and a half years, capital of the land we carpet-bombed for all the wrong reasons. How can I bicycle for pleasure in the place where my high schoolmates died because they weren’t lucky enough to be in college, and thus were ripe for the plucking by their local draft boards? And why? To contain Communism, of all gruesome follies! How infantile a concept was that?

So … mixed feelings. Guilt, relief, curiosity: call it dexiety, a blend of depression and anxiety …

And yeah, of course – excitement.

Black and white? Yes, and there’s a good reason why….

BLEEEEP! I’m in the middle of Hanoi trying not to get mown down by a teenage beauty queen on a motorbike (that’s her in the white cap veering at me) … or any of her thousand compatriots. They say Vietnam has a greater percentage of motorbike ownership per capita than any place on earth, perhaps as high as some 5.5 million for Hanoi’s eight million residents, and the frenzy of funneling them through the tight winding streets of the Old Quarter is a pedestrian’s scream dream. Made worse by the fact that they park them millimeters apart on the sidewalk so there’s no place to walk but on the already jammed streets. I’ve experienced what I thought was hectic traffic before in Bangkok and Sri Lanka, but nothing like this, ever.

The Old Quarter itself began being inhabited two centuries ago when natives had the brain-quake to hoist houses on top of stilts to keep them from the snapping jaws of the alligators in the swamp below. Today, instead of gators there are these gorgeous women on Harleys plunging through. And half of them are texting.

You know, here’s a thought. If I were texting on two wheels in traffic like this with red lights serving a suggestive function only, I hope I’d have sense enough to slow down when people try to cross. Not here. It’s full speed ahead, blaring and bleating all the way. The decibel level shreds your eardrums. The visuals fatigue your eyeballs. All intensified by the fact that the cargo they’re carrying in back — banana tree branches, refrigerators — is twice as wide across as the drivers are. There’s simply no way to calculate how much room I might have to move.

OK, so while I wait for a break in the onrush, I’ll stand here collecting a few first impressions:

DECAY. Stucco is crumbling off brick everywhere. Which doesn’t seem out of character for a place built in an alligator swamp. But on a purely aesthetic level, the decay enhances rather than detracts, like in Rome. In America we’re over-quick to patch or raze, but decrepitude can lend architecture a lovely texturing to give us a sense of time passing….

NARROWNESS. Not only the serpentine streets but the buildings themselves are skinny. With real estate taxes calculated on how much frontage there is, most of the stores and houses that open directly on the sidewalk are only ten or 12 feet wide, going up four or five stories high and back deep into hidden recesses behind. It’s called “tube housing,” and it brings to mind the hopefully obsolete native practice of swallowing coconut worms….

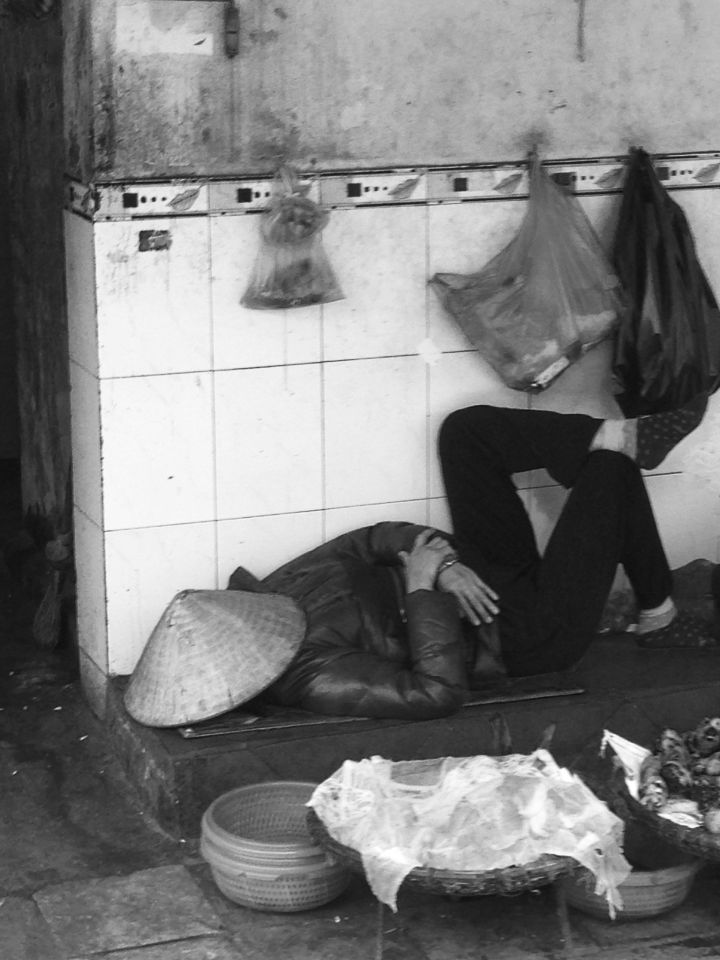

BLACK AND WHITE. Colors run riot: in-your-face flowers, shiny gift wrap, balloons. So why since I got here are all my photos coming out black and white? Maybe I haven’t mastered the settings of my new camera … or maybe it’s because of the war: what we call the Vietnam War but they call the American War. (As victors, they get to call it anything they want.) My vision is colored, or actually uncolored, by memories of the black and white newspaper photos of the 60s anad 70s. Tints and hues bleed away to leave only the grainy monochrome of that terrible time.

Right out of ’65, right?

STILL WAITING at that street corner to cross, five minutes later. I’ve made a few stabs at penetrating the flood of motorbikes and backed away each time, even though I’ve come to see that the drivers are skillful beyond belief. Not once have I seen anything close to a collision. They seem to have a sixth sense about where I’m going to step before I do, and where everyone else is likely to, as well. They’re preternaturally coordinated, with razor-sharp reflexes and nimble instincts. The closest I’ve come to seeing a bang-up is a faceoff between two drivers who stopped an inch short of heading each other, smiled politely, and resumed their opposite directions.

Picture kids racing around a playground – they almost never run into each other. Or forget playground –it reminds me of the way our soldiers used to describe encountering their counterparts in combat: with a genius for springing out of nowhere and vanishing again before they could say boo. It’s guerilla traffic, nothing less. I do believe that if our American generals had seen how light-footed they were, how uncannily agile and sensitive to nuance, they would have known they’d slaughter us in a jungle fight. As, of course, they did.

But please don’t yawn as you spare my life, will ya lady, swerving an inch from my kneecaps? Save me a shred of dignity?

CHECKING IN WITH MY DEZIETY, which actually seems better since this bout of traffic combat. Adrenaline helps. So how’s about a full-fledged traffic adventure? I flag down a warrior motorcyclist for a ride. “You’ll drive safely?” I ask.

“Don’t worry. If I kill you I kill me first!”

Dang speaks impressive English, from studying computer at university and cabbing on his motorcycle off hours. We talk as he veers. Twenty-five years old, he has a 72-year-old mother to whom he gives 40 percent of his earnings. His father was a soldier for the north — the enemy — but an American bomb robbed him of his left arm and the hearing on his left side, thereby reducing his marriageability. Was his father bitter against the Americans? “No, he always say ‘put the past in the past.’” And Dang’s mother went for him anyway. “Lucky for me so I was born!”

That’s the wreckage of the warplane in the water behind Dang’s head.

I’m so predictable. Now that I’ve become part of the madness, of course I want more beeping. Don’t spare the air horn, dammit! Dang drops me where I’ve asked him to, at B-52 Lake, so named because an American warplane was shot down into a small pond in the heart of Hanoi. The plane is still there, ugly steel reminder in stagnant green water. I say goodbye to Dang and walk the perimeter alone. At the far end I come across a trio of old ladies selling snacks who indicate they were there when the plane went down – saw it with their own eyes. They angle their hands downward to indicate how the plane fell, making sound effects to represent the crash. “Was it a close call?” I ask, wiping my brow to show what I mean. The one with black shellacked teeth gets it, wiping her brow and flicking off the pretend sweat. Yup, close call.

Witnesses to the crash. These three saw the B-52 crash in 1972. Notice the black shellacked teeth of the woman on the left, a sign of beauty caused by eating betel nuts and applying black resin.

AND NOW MY OWN CLOSE CALL. Now I need a ride back to the Old Quarter, clear across the city. It’s rush hour and the guerilla traffic has increased exponentially. More and more outlandish things are on the backs of the motorbikes: a cage with three piglets inside, then the carcass of a full-sized dead pig, its uncovered body flayed down the middle into two equal parts that lie astride the back seat, open to the road dust. I simply cannot find an opening in the traffic. It would take a leap of faith to penetrate, and I’m not in the mood for leaping. On a tree growing out of the gutter to my right, a large insect seems as stuck as I am, its front claws gripping the bark. It’s like a nuked version of a praying mantis: triple-sized and pinkish-blue. We’re paralyzed, it and I, until a 90-something old lady takes pity, clasps my wrist with two fingers as though taking my pulse, and leads me across the street. No fanfare, she just steps into it. The traffic obliges.

Great, I’m on the other side of the street. Now what? I wave my arm to get a ride, but this merely puts the arm in jeopardy. (I would really hate the irony of losing my right arm to balance out the loss of Dang’s father’s left one.) Darkness has happened, thickening the smog. In my New York blacks, I feel invisible. Eventually I turn into the tiny motorcycle shop behind me, a mom-and-pop operation, and throw myself at their mercy. Do they have any idea how I can get a ride? (Body English: it’s miraculous how it works all over the world.) Such kind faces: they indicate that I shouldn’t worry, go to the back of the shop, and gently call upstairs. Soon their son comes down, obviously just wakened. “I will take you,” he says sweetly, snapping on a motorcycle helmet and handing me one as well. I make an abject show of thanks, double-clasping everyone’s hands. And we’re off. “How much can I pay you?” I shout to my savior.

“Not necessary,” he shouts back.

Astounding. Yet this is how our species is, I’ve found. All over the world, more generous than we give ourselves credit for. But also more mystifying. Two blocks later, my savior drops me off. What happened to the rest of my ride, the cross-the-city part? I don’t know, but it’s a major intersection where cabs bob along like flecks of jetsam in a flashflood. Ten minutes later I manage to pile into one, relieved. But the cabbie doesn’t know the words “Old Quarter.” He doesn’t know when I spell it out for him. He doesn’t know when I deploy my body English. He doesn’t know when I pull out a map and point to it: there, right there, the Old Quarter!

He produces a feathered toothpick and patiently begins filing his teeth. And there we sit in the middle of the intersection, cars shrilling as they pile up behind us, the two of us mulling our conjoined fates, not so much contemplating the chaos as simply letting it marinate for as long as it takes.

Let’s leave it right here for the night, shall we?

*****

MORNING! And time to meet the team. Like thousands of others, I’ve been salivating over the ads for Pedalers Pub & Grille in the backs of such mags as Outside for years. I’ve been enchanted by the defiantly contrary name as well as the description of its adventurous itineraries. [Contact info for Pedalers can be found in a P.S. at the end of this article.] “Pedalers Pub & Grille is not a restaurant,” begins its website, and indeed it isn’t. It’s an innovative bike tour operator offering longer-type bicycle trips in Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Africa, Alaska and Hawaii, including this ten-day beaut in north and central Vietnam. What makes them “innovative”? Their flexibility, for starters. No other travelers happened to have signed up for this particular trip except my girlfriend and me (Jamie joined me here last night on a later flight, about the time I made it safely to my hotel), but instead of cancelling on us as any ordinary outfit would do, they’ve simply accommodated, giving us our own private driver and guide for the duration.

And what a guide.

“Hello, my name is Phan Van Dan,” he says, shaking our hands in the hotel lobby. “I am small but very strong. See, very strong!,” he says, flexing his bicep. “Half a peanut!”

So with that he is “Peanut” to me. He seems to like the nickname though, truth to tell, he’d probably like any nickname. He’s so upbeat and sunny, it’s hard not to find him lovable from the get-go. He’s also extremely knowledgeable, as he is the first to point out.

“I have been guiding 18 years, and know every road in Vietnam!” he exults, pulling out a map and penning out our route for the next ten days. “Ready to start?”

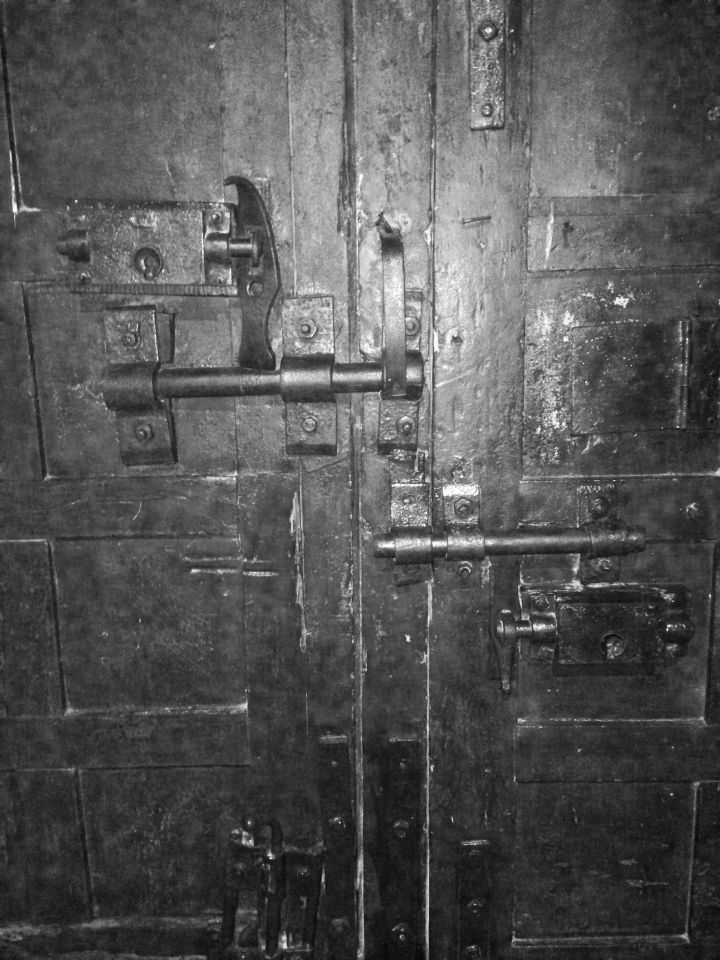

Hoa Lo Prison is our first stop. Famously nicknamed, with admirable gallows humor, the "Hanoi Hilton" by some of the 600 American POWs imprisoned here between 1964 and 1973, it’s where McCain served his time, much of it in solitary and all of it in pain. I lost a measure of respect for the man during his 2007 presidential bid when he sang an impromptu but highly inappropriate tune to the words of the Beach Boys song Barbara Ann (“Bomb, bomb, bomb Iran”), but it must never be forgotten that he declined to leave ahead of his mates, when offered clemency. Walking through his prison, I decide to cut him a little slack. The door to the cellblock itself is enough to dispirit anyone.

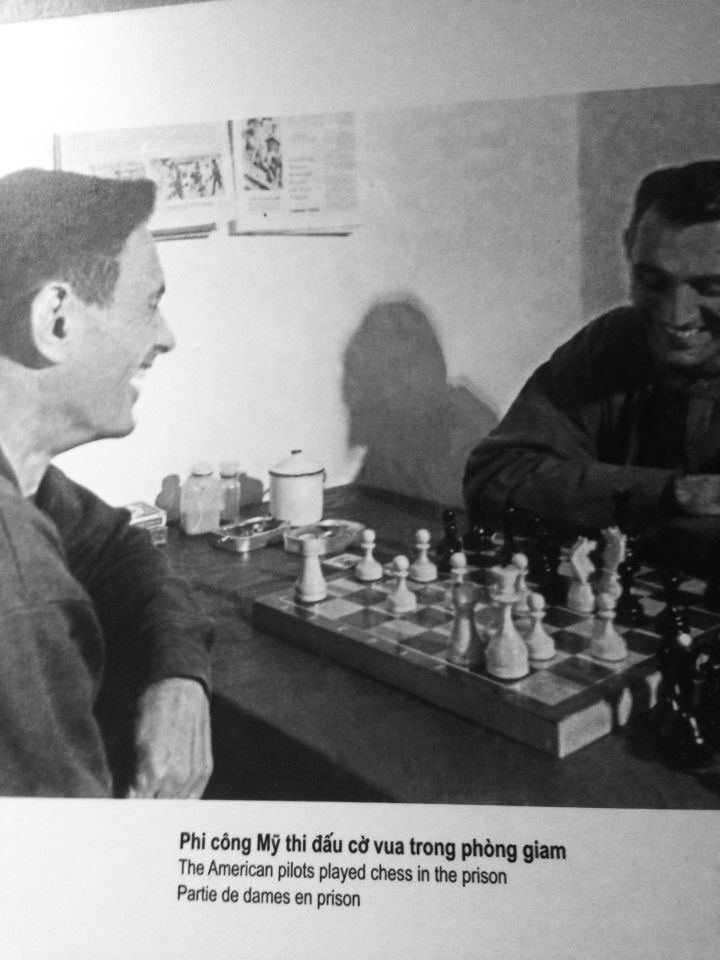

Add to that the fact that the powers that be painted the interior of the prison with black tar to add even more gloom. It’s 72 degrees outside and I have to put on my bike jacket to ward off the shivers. With this kind of chill, you can feel on your own skin how phony the propaganda photos are:

*****

NEXT UP IS THE WOMEN’S MUSEUM. “Vietnam has a long history of warrior women such as the ‘tiger general’ who fought with courage,” say the captions. According to the literature, women comprised 40 percent of the fighting effort in the American War — capturing enemy soldiers, digging trenches to obstruct enemy vehicles, acting as spies, even directing battles. I don’t need convincing; I ‘ve seen them on motorbikes.

Outside the museum, the incorrigibly flirtatious Peanut demonstrates that it’s not all as somber between the sexes as the museum has us believe. “Hello, I love you, won’t you tell me your name,” he sings to just about any pretty woman we pass on the sidewalk. I’ve always preferred the Doors to the Beach Boys anyhow.

“Kill evil to liberate beloved homeland,” is the theme, succinctly put, of our final destination, the Military Museum. Bamboo spikes, grenades, and all manner of killing equipment are put to effective display. And more commonplace stuff, too: Vietcong sandals made from the rubber tires of captured American trucks, harmonicas to hearten the wounded. It’s always odd how ordinary household items become aggrandized when mounted behind glass. Outside the museum, children do what children are meant to do all over the world: bring history down to size. They climb and play all over the captured American tanks, rusty from decades of rain. Victory to the victors, as they say. Or something like that.

THAT NIGHT AT THE HOTEL, I think about the day. Well, I think about the hotel, first of all. It’s a far cry from the Hanoi Hilton, or any normal Hilton, offering good service with none of the obsequiousness that so often goes with it. I don’t know about you, but I can’t stand it when a bellhop insists on twisting open the bottle cap for me or the waitress asks me six times how I’m enjoying my meal. The choice of this hotel reflects the down-to-earth sensibility of Pedalers, is my thought. Once again, my kudos.

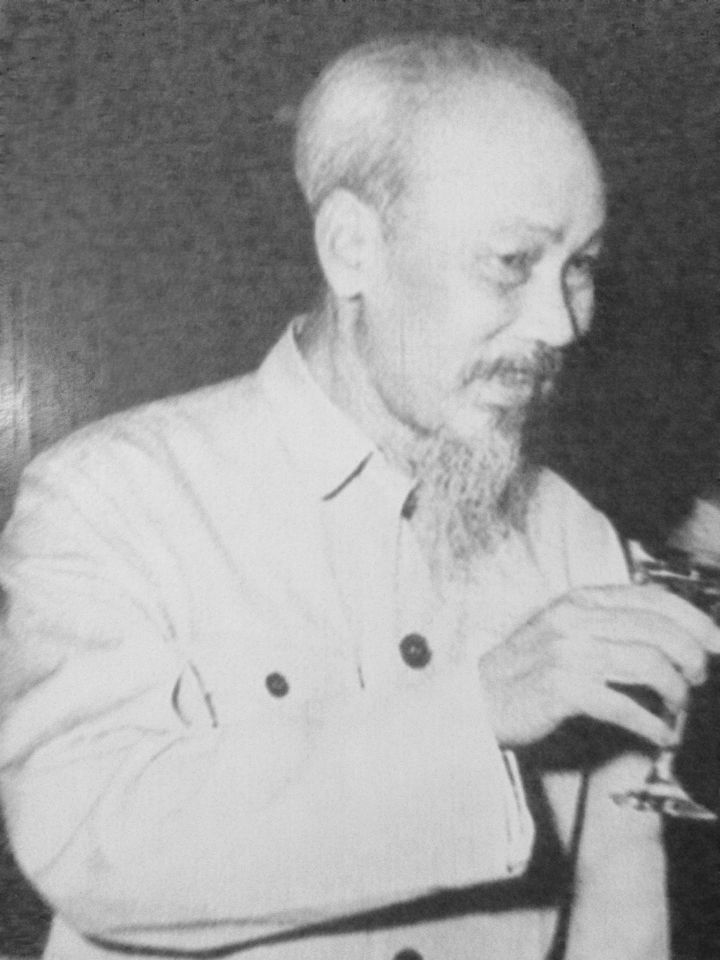

It’s when I‘m in bed, a little later, that I think about the day — about Ho Chi Minh, for one thing, whose picture popped up about two hundred times today, like an emaciated version of Colonel Sanders without the forced cheer.

Such a gentle, refined face, yet he led one of the bloodiest wars of attrition ever fought. A complex man: in his youth he wandered the world, putting in time as a pastry chef under Escoffier in London’s Carlton Hotel, and even working in the dockyards of Brooklyn for a spell. I’ve been reading about the War he conducted, Herr’s “Dispatches” and a few others. How come I never let it truly penetrate my consciousness until now? Take a listen:

“Twenty yards in front of us men were running around totally out of their minds. One man was dead … one was on his hands and knees vomiting some evil pink substance, and one, quite near us, was propped up against a tree … making himself look at the incredible thing that had just happened to his leg, screwed around once at some point below his knee like a goofy scarecrow leg. He looked away and then back again, looking at it for a few seconds longer each time, then he settled in for about a minute, shaking his head and smiling, until his face because serious and he passed out.” [“Dispatches,” p. 32]

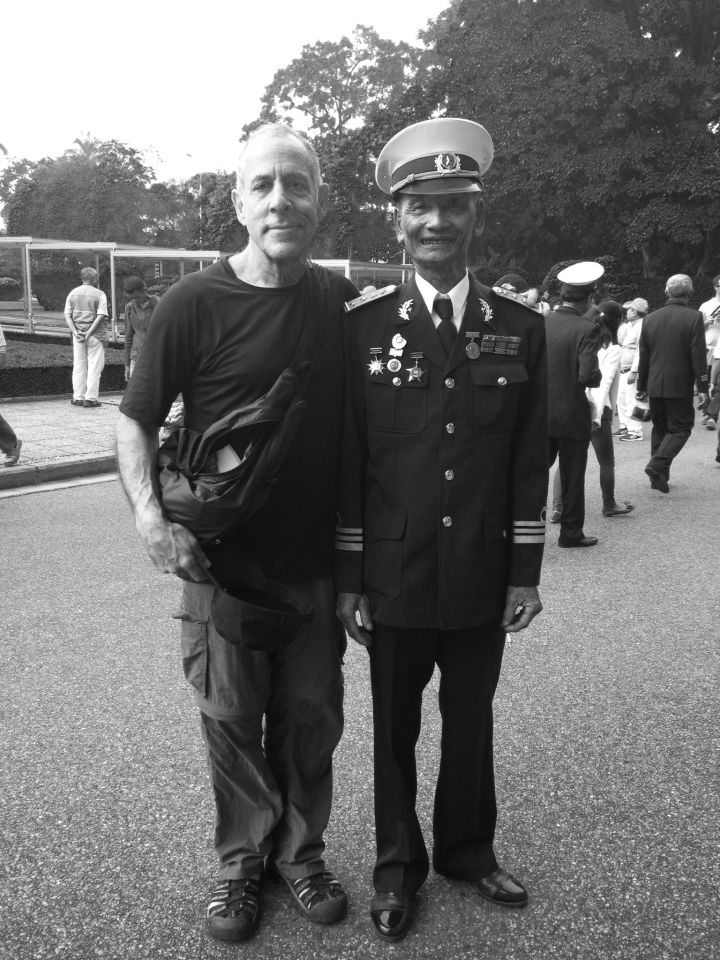

I think back on Ho Chi Min’s house that we saw today, giving off a profound air of tranquility. I think back on seeing him lying in state, white as a stalk of blanched asparagus. I think about the much-decorated former North Vietnamese pilots I met outside his mausoleum. Jamie took a picture of one of them with my arm around his skinny shoulder; he did not put his arm around mine. Bone thin, he was as hard-core as they come, with yellow teeth bared in a strained smile – all skeleton beneath his starched uniform. Right there, with my arm around his scraggy shoulder, I felt the War: spit-shined shoes below and ice-cold rictus above, this was a man who could eat bullets for breakfast. Yet later at the gift shop there he and his comrades were, laughingly buying HCM keychain souvenirs just like everyday tourists.

(“Not everyone in love with Ho,” Peanut had quietly confided to me, seeking to give me a more balanced picture outside the gift shop. But he had looked around before he said it, making sure he wasn’t overheard. For all the lightheartedness of Peanut’s manner, that single look reminded me it is a totalitarian society. Forget that at your peril.)

Here are a few grabs of those kinda creepy Air Force pilots:

*****

PEANUT IS A MORNING PERSON, APPARENTLY – already in a joking mood next day at dawn. “How are you tomorrow?” he greets Jamie and me as we enter the dining room. And here is how we’re supposed to answer: “I am good yesterday!”

He cracks himself up. But it’s pretty damn existential stuff, if you ask me.

I was right about the hotel: it is a good one. The staff is attentive in a low-key manner that feels genuine. “It’s good to have a visit and also a good home to come back to,” says the staffer Jenny, and I choose to believe she means it. Look, she’s even opened the kitchen early so we can get a jump on our first day of biking.

Outside, we inspect the bikes before they’re stashed in the van: Trek 4300’s with aluminum frames, SunTour front suspension forks, and Shimano Acera drivetrains. (Trek used to offer the 4300 in the US, but no longer.) Eminently ride-able.

As we drive out through the drab environs of Hanoi, it’s all grey concrete and exhaust fumes, scooters and trucks. Soon we pass banana trees coated with road dust. Old Vietnam is everywhere: bamboo ladders and railroad bridges that look like they came out of an Erector kit. But there are also signs of emerging prosperity, and nowhere more than with the nouveau gaudy houses, outsized McMansions that look even more ludicrous than in America because they reduce their frontage tax by sprawling upward instead of sideways in a confection of wedding cake touches: balconies, buttresses, third floor swimming pools.

Northwest of the city a couple of hours, we begin biking past a field of wild lemon grass in the mountainous province of Hoa Binh. It’s good to engage the muscles and turn off the brain for a while. In the water of the placid rice paddies that reflect the jutting mountains, both men and women still wear those conical hats (the Non La) that have been worn for the past 3,000 years. I try one on and understand the secret to their longevity: without compromising your vision, they provide a 360-degree perimeter of cool shade — advantageous when you’re bent over 13 hours a day under a murderous sun.

Peanut knows we want to get off the beaten path as much as possible and he leads us down a back road overlooking Hoa Binh Lake. Soon we are in a village with so little traffic that a group of five boys are playing hacky sack on the main street, using a sack that’s like a badminton birdie with plumes. Quickly there are 8 boys, and then 12, including me. Girls cover their mouths and giggle as I make a fool of myself. Fat ducks quack as they squish across a mudflat by the road; water buffaloes sullenly shake the bells around their neck, an old lady sucks pensively on sugar cane. But all I see is the War. These beautiful faces shrieking in terror as airplanes strafe. A girl with outstretched arms running naked after napalm has burned her clothes off. I shake my head. We never attacked this village, I’m told. Near but not here.

Jesus, is all I can say.

We earned our rest today. After a total of 45 miles, we reach the city of Mai Chau and a luxurious resort called the Ecolodge. Lavish wooden huts descend the slope beneath us. In the distance is a silhouette of three young women jumping rope, backlit by the orange sun setting between the bumpy mountain skyline. A life-affirming sight.

“Good jumping!” I call.

“Thank you! Care to join us?”

I pass. But lordy, I can’t help thinking, how the world does keep sending life to the living!

Somewhere in the distance past this lodge are three young women jumping rope.

*****

“HOME DEPOT!” calls out Peanut from his bike in front of me next day.

“Home Depot?”

“Hmong people!” he repeats. I misheard him. And sure enough, we are in a village of Hmong: their colorful embroidered clothing set them apart. We’re biking to an ethnic fair of the sort I ordinarily dislike. Too often they seem zoo-like — see the natives in their exotic finery! — even though I know they help put cash into the hands of the local population. But this one is tasteful, as these things go. I don’t find something like a rayon scarf from Bangladesh mixed in, as I sometimes do at these things.

And there are always the quips of Peanut to keep us entertained and informed. Turns out he knows no fewer than eight languages, and if he’s as creative in the others as he is in English – he calls a church a “Jesus office,” and a gas station a “car bar” — he’s something else. Well, I already know he’s something else. I feel lucky to have him clearing my head, because my head is doing some unsettling things.

Our philosopher king, the incomparably existential Peanut. “How are you tomorrow?”

My reaction to the landscape, for instance. Biking the side roads again, I find the scenery baffling. On the hand, it’s beautiful. No question about it. “Six shades of green, motherfucker, tell me that ain’t something beautiful.” [“Dispatches,” p. 106] On the other hand, it’s haunted by ghosts of the War. How could such carnage have happened in such a peaceful-seeming setting? “The lush green vegetation of the countryside – royal palms, banana stalks … If you didn’t know better, you would have thought you were in paradise, not hell.” [“Pugilist at Rest,” p. 38] Shafts of dusty sunlight ray down between the mountain peaks as I try to banish disturbing images from my head.

For a time, we’re stuck behind a truck hauling bamboo through a bamboo forest. They’re going to make a lot of chopsticks from that haul. For another time we’re stuck on the Ho Chi Minh Highway, ugly as sin. I’m surprised by how negative my reaction is, but this “trail” was the main route that supplied the Vietcong, right? I guess old propaganda dies hard. It’s high time I read a more objective account:

“People on the trail had to contend with almost constant bombing. By early 1965, aerial bombardment had begun in earnest, using napalm and defoliants as well as conventional bombs, to be joined later by carpet-bombing B-52s. Every day in the spring of 1965 the US Air Force flew an estimated 300 bombing raids, and in eight years dropped over two million tonnes of bombs…. So much firepower was unleashed … that for years nothing would grow in the impacted, chemical-laden soil…. Up to 30 percent of ordnance … failed to detonate on impact and … these have, since 1975, been responsible for up to 10,000 deaths and injuries.” [“Rough Guide,” p. 335-336]

Twilight finds me in a warren of streets. Public loudspeakers come on: the government giving the news, another reminder that we are in a centrally controlled society. Shops close, banging down rickety metal grills. With darkness the wind rises, bringing bugs to hit our faces as we pedal. “It was at dusk, those ghastly mists were fuming out of the valley floors, ingesting light.” [“Dispatches,” p. 96]

By the time we’ve attained our lodging for the night, I have a full case of the willies. The Emeralda Resort is nothing less than a hallucination of hospitality, one of the prettiest properties I’ve seen in Asia, lit up like a teak temple. Jamie trots off to get a massage that she says rivals the best she’s had anywhere. Should I allow myself a body massage in a place where so many bodies were lost? It feels decadent but I do it anyway. And you know what? It is good.

*****

BUT THE PEOPLE. Again and again the question arises: Why is everyone so nice to us after what we did to them? We lost 57,000 of our own soldiers, but the death count of Vietnamese is conservatively estimated to have been more than a million. Even 40 years later, I occasionally glimpse people hobbling about with misshapen limbs; the result, I’m told, of their parents passing down genes whacked by Agent Orange. How are they able, as my Hanoi cabbie’s father said, to “put the past in the past?”

On the ride to the ancient capital of Hua Lu, I work out some theories.

— “It wasn’t you, it was your government” is a refrain I’ve heard several times. Maybe that dichotomy is easier to swallow in a non-democratic society that isn’t responsible for choosing its leaders.

— That same American government has bettered its relationship with Vietnam in the intervening decades so much that the US is now our former enemy’s largest trading partner. So much for never doing business with Communist countries

— It seems blasphemous to think, but war may not seem as horrific to people who’ve experienced almost non-stop conflict for century after century.

— They won! And maybe it’s easier for victors to forgive. Think how bitter much of the American South still is, compared with the North, so many years after the Civil War.

— It’s a young country, with 60 percent under the age of 35, and it’s axiomatic that the young disdain ancient history. I ask a 20-something if she knows when the War took place and she replies, “Ummm, 1800s?” In fact, it may be a healthy sign of adolescent rebellion to them to be so pro-American they love every pair of blue jeans we throw at them.

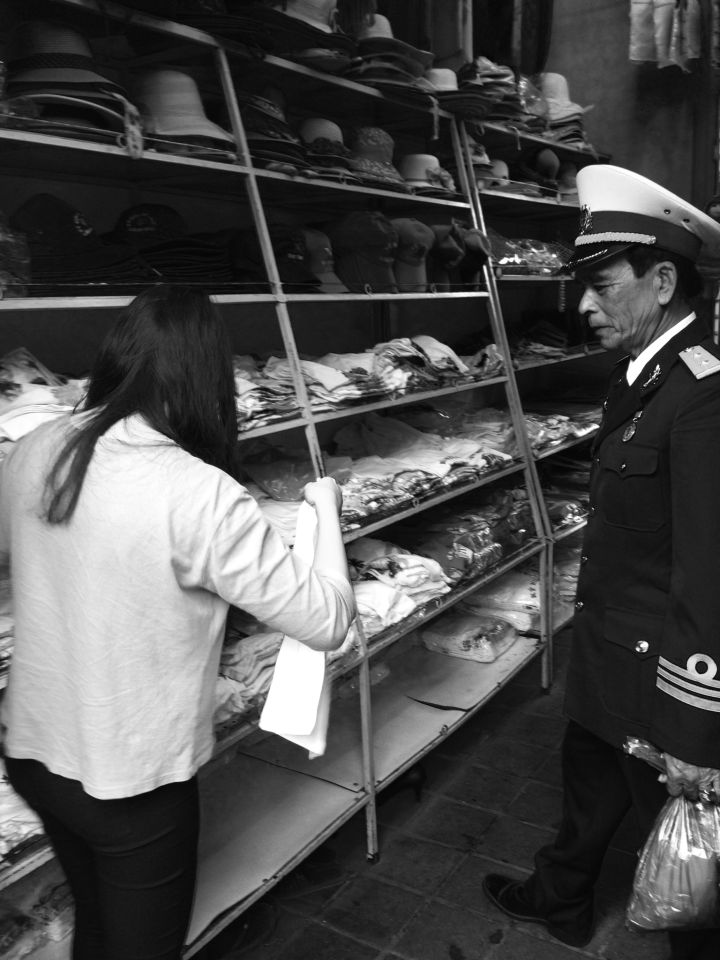

Given all this, I keep trying to find an old North Vietnamese soldier to talk to, but don’t get very far. In the cities, they sit outside the souvenir shops and North Face outlets smoking the old way, with three fingertips on their fags, enjoying the songs of Lionel Ritchie and Celine Dion and Rod Stewart belting out from the interiors. Something stops me from approaching. After all, they do seem to favor jungle-green bike helmets resembling army headgear. Or am I reading too much into it?

One old-timer I manage to talk with is our driver, but he was excused from the War because his seven older siblings were already serving. Anyway, he’s more interested in talking about Jamie’s left-handedness, something he’s never seen before because when he was growing up, southpaws were punished until the condition was “corrected.” That, and he prefers chatting on his iphone that has a plonkety-plunk ringtone like the slap bass theme song for Seinfeld.

So does no one care to remember? On a road deep in the jungle, we pass a small memorial hacked out of the undergrowth. Peanut translates the inscription: “The country remembers them and we are grateful forever.” But do they remember and are they grateful? Do we and are we, about ours?

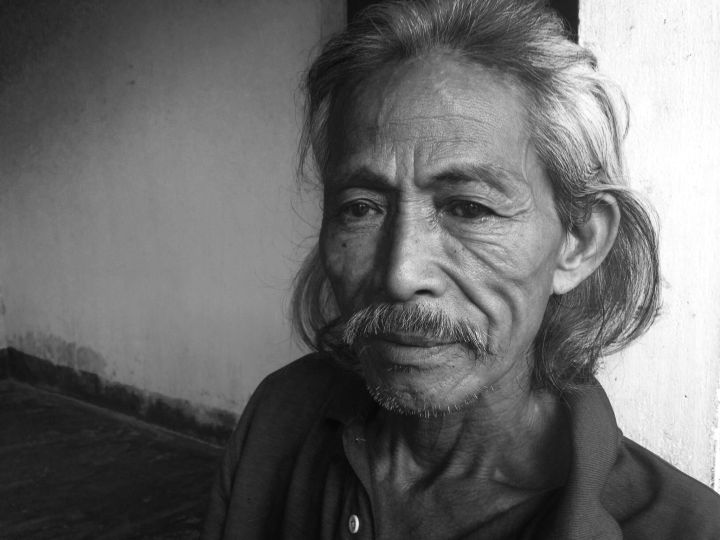

Some pictures of beautiful old-timers:

*****

WHAT GOOD does it do anyone that I am starting to care, forty years too late? It’s a mystery why it’s taken me this long to come to grips with one of the seminal events of our epoch. In yet another luxury resort I am wrenched from sleep with what feels like a boulder turning slowly in my gut. Food poisoning? But we’ve been eating amazing well: mustard greens with garlic and ginger, crispy pancakes stuffed with shrimp and bananas under a peanut sauce, the best baguettes in Asia (courtesy of the French heritage). No, the food is why so many people from the mountains around here routinely live past 100. It’s deziety, is what it is, compounded by some bad water I must have drunk along the way. Soon it’s a full onslaught of the runs. A classic night follows: Diarrhea and bad conscience

Why didn’t I protest more? Here I am on a spectacular bike trip run by one of the best travel outfits in the world, yet I’m tormented by the question. I was cloistered by college, of course, but so were thousands of other students who managed to stay engaged. It’s not like I didn’t know: I hitched cross-country twice in those years and heard firsthand horrors from newly released vets who picked me up and needed someone to vent to. I did a token amount of protesting, standing vigil by the flagpole on the green and mounting a few guerilla theater events, but not nearly what I should have….

“US OUT OF VIETNAM!” The placards parade past my eyes again in the hotel bathroom as I recall our day back at the Hanoi museums. Wall after wall, room after room showed demonstrations in Australia, Japan, Mexico, Canada, Venezuela, Uruguay, Egypt, India, not to mention virtually all of Europe. Where was I? Was I really so involved in my little romances that I couldn’t be bothered to march on Washington? Were the petty dramas of my personal life so consuming I couldn’t be bothered to see that the domino theory was criminally asinine? (Nations falling to Communism one after the other like dominos? Really?) Shameful questions assault me in the bathroom. Was I really so averse to group activities in those days that I couldn’t even join a noble effort like the antiwar movement? Worse, was I bored by the War? God forgive me, but it was always on – every time you opened the paper or turned on the TV. It was like, change the channel already….

Disgraceful thoughts, finally catching up with me. I take a Valium to soften them – the largest dose I‘ve taken since my college sweetheart was cheating on me back in the early 70’s, at the height of the War, come to think of it. But more of the war’s madness is hitting me now, along with my own personal sense of failure. I’m incensed for all the time I wasn’t incensed. I’m mortified for all the time I wasn’t mortified. Is there anything I can do now to make up for it.

The deziety ebbs and flows….

*****

RELIEF. An early morning flight brings us back to our comfy hotel in Hanoi.

“Ah, hello Mr. Daniel, welcome home. We heard you had a little trouble with your throat?”

“No, my tummy, but it’s fine now. How did you know?”

“Your excellent friend Mr. Peanut send word. And so we prepare a little tea to settle you, maybe with a little lemongrass and honey?”

Jenny (to my left) is concerned about me, but the color has returned!

*****

AND THIS IS WHERE I’LL LEAVE PART ONE. Happy to be “home,” and ready to leave the north next day for the second portion of our bike trip in the central area of Hue and Hoi An. You can see from the photo above that the hotel staffer Jenny is a bit concerned about me, but you can also see that the color has returned to my photos. I either pressed the right button on my camera by accident or am finally shedding some of my monochromatic thinking as I come to a more nuanced, less black-and-white understanding of what this country is all about….

I’ll include a few photos from part two of my dispatches to give you an idea of what’s to come.

Witnessing the six shades of green.

Witnessing the six shades of green.

Old-timers and new, getting in the swing of things.

Old-timers and new, getting in the swing of things.

Seeing more moods of the people.

Seeing more moods of the people.

Confronting the Awful Names: Vietnamese take pictures of themselves over the ruins of an American fortification

Confronting the Awful Names: Vietnamese take pictures of themselves over the ruins of an American fortification

in the cloudy mountaintop above Danang.

The North Vietnamese graves are still there….

The North Vietnamese graves are still there….

Which is why it’s so spooky to see old battlefield names like Danang used in conjunction with luxury tourist accommodations.

Which is why it’s so spooky to see old battlefield names like Danang used in conjunction with luxury tourist accommodations.

The journey ends with three glorious days on Ha Long Bay…

The journey ends with three glorious days on Ha Long Bay…

Exploring craggy caves by kayak under the guidance of Mr. Peanut.

Exploring craggy caves by kayak under the guidance of Mr. Peanut.

Meeting young people (60 percent of the population) who have very little knowledge of the war.

Meeting young people (60 percent of the population) who have very little knowledge of the war.

And me taking a leap into the unknown (I must be feeling better)….

P.S. A word about Pedalers Pub and Grille. I've been with a lot of biking groups over the years, but this was one of the best. It was apparent from day one that they obviously love doing this. Pedalers consistently chose interesting, off-the-beaten-path bike routes. They selected restaurants we never would have found on our own, where we had some of the best food we’ve ever eaten anywhere: not only grilled goat with crinkle cut French fries (!) but mustard greens with ginger and garlic as well as pancakes stuffed with pineapple under a condensed milk sauce. Who knew condensed milk could be so savory!? We never felt rushed or pressured, and were encouraged to make our preferences known every step of the way. The lodging was far more luxurious than we expected, yet the whole trip was quite a bit more economical than others we investigated. Contact: tours@pedalerspubandgrille.com; phone in Gainesville, Florida: (352) 353-8712.

Tell Peanut I said hi.

Comments