Central America forms a bridge literally between North and South America, which throughout its three million year history has served as a natural biological passageway between the two continents. In the last century, however, much of that corridor has been destroyed by farming and urbanization.

Biologists have determined that biological corridors are one of the most effective methods of conserving biodiversity to maintain genetic fluency between populations of species and prevent against their possible extinction. The concept of wildlife corridors has been around for many years, but in Central America it is being realized on a monumental scale.

In the 1990s, the eight governments of the region (Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Salvador, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and Mexico) agreed to coordinate their efforts to prevent biodiversity loss and create a huge system of interconnected parks, reserves and wildlife corridors that seamlessly link North America to South America. The vision is for an immense biological corridor connecting the forests of southern Mexico to those in the rest of Central America, all the way down to the Panama Canal.

In the 1990s, the eight governments of the region (Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Salvador, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and Mexico) agreed to coordinate their efforts to prevent biodiversity loss and create a huge system of interconnected parks, reserves and wildlife corridors that seamlessly link North America to South America. The vision is for an immense biological corridor connecting the forests of southern Mexico to those in the rest of Central America, all the way down to the Panama Canal.

Originally called the “Path of the Panther” and promoted by the Wildlife Conservation Society and by Dr. Archie Carr, founder of the Caribbean Conservation Corporation (now called the Sea Turtle Conservancy) that protects sea turtles on Costa Rica’s Caribbean Coast, the project was adopted in 1997 by Central America’s governments and changed its name to the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (MBC).

The scale of the undertaking is massive. So far, Costa Rica is the only country that has elected a strategy of working with community and environmental organizations to create a chain of local biological corridors, using tax incentives, preservation easements, education, decentralized administration, partnerships with international organizations, and outright land purchases. As a result, Costa Rica has experienced a higher level of success in establishing the MBC than other countries in Central America.

Nevertheless, environmental destruction by real estate developers presents a serious threat to the environment. Additionally, if overall funding from international agencies is diminished or discontinued in the near future, it could mean the death of the entire Central American biological corridor project.

Costa Rica Central-Southern Pacific biological corridor

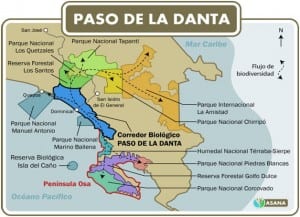

A long chain of coastal mountains extends down Costa Rica’s Central Pacific Coast to the Southern Pacific and the Osa Peninsula. These mountains also stretch inland up to the Cordillera Central (Continental Divide) that runs like a long spine from north to south down Costa Rica into Panama.

A long chain of coastal mountains extends down Costa Rica’s Central Pacific Coast to the Southern Pacific and the Osa Peninsula. These mountains also stretch inland up to the Cordillera Central (Continental Divide) that runs like a long spine from north to south down Costa Rica into Panama.

Here is one of Costa Rica’s largest biological corridor projects. Private conservation organizations are working to link the Osa Peninsula Biological Corridor in the south with the Inter-oceanic Biological Corridor, which spreads from the Savegre River Valley in the Central Pacific to the central mountain range and La Amistad International Park into Panama. Included in this area are the Tapir’s Path Biological Corridor near Dominical, the Rio Naranjo Biological Corridor and Portasol Biological Reserve, occupying the space between three of Costa Rica’s most well-known national parks – Corcovado, Manuel Antonio, and Los Quetzales.

Portasol Biological Reserve

The Portasol Biological Reserve is unique because it is part of the Portasol Rainforest & Ocean View Community land development. Real estate development and conservation of biological corridors might seemingly be juxtaposed, but in Portasol’s case, they work in harmony.

The Portasol Biological Reserve is unique because it is part of the Portasol Rainforest & Ocean View Community land development. Real estate development and conservation of biological corridors might seemingly be juxtaposed, but in Portasol’s case, they work in harmony.

“It is a radically different concept of real estate; very different from other private reserves in Costa Rica,” remarks Olivier Chassot, Ph.D., land owner at Portasol and Executive Director of the Tropical Science Center in Costa Rica. “Portasol is a good example of what a green economy is. The value of Portasol is in the trees and rivers and animals, and not its houses or hectares.”

Portasol is located in the coastal mountains half-way between Manuel Antonio and Dominical, right near Playa Matapalo and the Savegre River. Set on 1,300 acres of pure rainforest along the Portalón River Valley, the sustainable residential community has building lots for sale and also offers tourism hospitality with unique vacation rentals. Two hundred acres of virgin forest near the top of the mountain has been set aside as a private nature reserve. The development is part of the Inter-oceanic Biological Corridor.

Portasol is located in the coastal mountains half-way between Manuel Antonio and Dominical, right near Playa Matapalo and the Savegre River. Set on 1,300 acres of pure rainforest along the Portalón River Valley, the sustainable residential community has building lots for sale and also offers tourism hospitality with unique vacation rentals. Two hundred acres of virgin forest near the top of the mountain has been set aside as a private nature reserve. The development is part of the Inter-oceanic Biological Corridor.

“Portasol is important because it is perpendicular to the mountain range and the sea, in its widest part,” explains Chassot. “Birds, insects, animals and trees can move in the corridor and adapt to climate change by moving up with the warming trend.”

Chassot noted that Portasol has a good elevation gradient with many different ecosystems. “Portasol has a great potential for biodiversity because of its widely varied environment from flat land to high mountains, valleys, rivers, creeks and forest,” he said.

Chassot and his wife, Guisselle Monge Arias, Ph.D., both work with numerous conservation organizations in Costa Rica and Central America – the Tropical Science Center (one of the most influential institutions in Latin America in science and conservation), the Great Green Macaw Research and Conservation Project in Sarapiqui, the San Juan-La Selva Biological Corridor near Sarapiqui, and the Mesoamerican Society for Conservation Biology. They purchased a 1-hectare lot at Portasol in January 2013.

Chassot and his wife, Guisselle Monge Arias, Ph.D., both work with numerous conservation organizations in Costa Rica and Central America – the Tropical Science Center (one of the most influential institutions in Latin America in science and conservation), the Great Green Macaw Research and Conservation Project in Sarapiqui, the San Juan-La Selva Biological Corridor near Sarapiqui, and the Mesoamerican Society for Conservation Biology. They purchased a 1-hectare lot at Portasol in January 2013.

“We were really delighted by the forest environment,” said Chassot. “We fell in love with the place. The sheer beauty is amazing … water everywhere, the trees. It’s a real holistic development.”

Chassot and Monge agree that Portasol is a model project on land use, offering large properties and a nationally registered ecological easement. The development has a rule that owners may only build on 15% of their land and must preserve the rest in green space. A conservation easement binds heirs and future landowners to comply with the easement’s terms, ensuring that conservation purposes are met forever. Conservation easements were pioneered in the United States. Costa Rica, advised by The Nature Conservancy in the early 1990s, was the first country in Latin America to develop conservation easements and land trusts.

Chassot and Monge agree that Portasol is a model project on land use, offering large properties and a nationally registered ecological easement. The development has a rule that owners may only build on 15% of their land and must preserve the rest in green space. A conservation easement binds heirs and future landowners to comply with the easement’s terms, ensuring that conservation purposes are met forever. Conservation easements were pioneered in the United States. Costa Rica, advised by The Nature Conservancy in the early 1990s, was the first country in Latin America to develop conservation easements and land trusts.

“We have been promoting ecological easements in our work,” noted Chassot. “It is great that our neighbors will have to respect the terms of the easement and the land will be protected for our kids and grandkids, etc.”

Added Monge: “There is much more awareness in Costa Rica today toward nature. People are thinking about preserving the natural resources of the country. Costa Rica is the most advanced nation in Central America in preserving its biological corridors.”

By Shannon Farley

Comments